Just What Is Mike's World?

I wrote the Mike's World humor column for Midwest News from May 2005 until January 2014. Deciding to end the column was not easy, but sometimes even good things must end.

Many of my articles recall events that took place when I was a kid growing up in Fort Branch, Indiana. I've learned many of life's Great Truths during my childhood, and I'm convinced it's my duty to share those Great Truths with people everywhere whether they want me to or not.

Now, you won't find Mike's World on traditional maps. I've discussed this oversight with map makers, and they claim they can put places on a map only if they are a hundred percent reality based . . . like Gary, Indiana, and Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania. When I point out that they managed to put Hollywood, California, on the map, they respond by saying they made an exception for California in general, but that's the only exception they're willing to make.

But don't worry. You can always get to Mike's World by ordering my humor book, Tales from Mike's World.

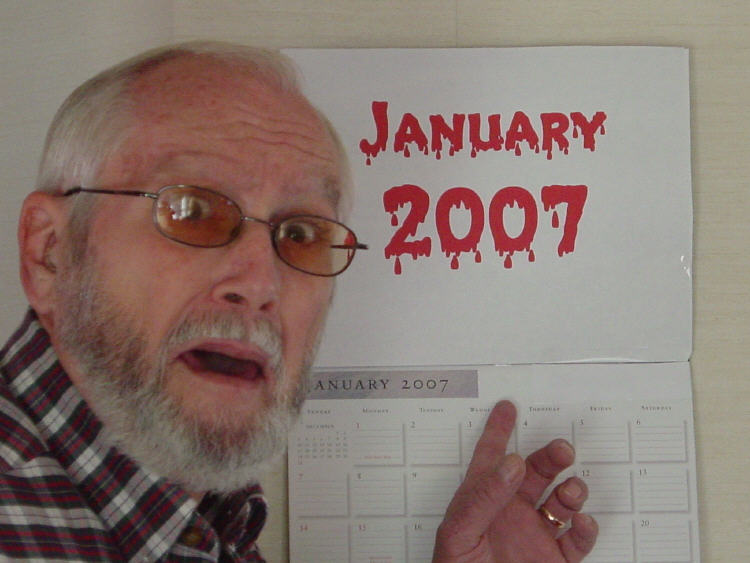

Pictures accompanied many of my Midwest News articles. Below are pictures from four of my articles as they appeared on Midwest News.

Here's a sampling of articles.

Mike's World revisited

Article Date published on Midwest News

The Belt and the Penny December 2008

A Boy Named Bird Legs October 2012

Lessons Grandmother Taught Me January 2013

A Long Overdue Thank You November 2013

Maybe You're Left-Handed September 2012

Scouting, fate, and the presidency April 2006

Write Your Name on the Old Rusty Spade June 2013

The Belt and the Penny

"...and for the next five decades, I found comfort in knowing all my classmates had also experienced the belt and the penny."

Televised news reports of a recent college hazing incident kick started my memory, and soon it roared down dusty back roads it hadn’t traveled in years. When it reached its 1957 destination, it popped wheelies around my long-since demolished high school, creating a cloud of dust full of blurred faces and vague recollections of the hazing team my freshman year. Although the team, which I now refer to as the Belt and the Penny Society, wasn’t school-sponsored, it was a talented one—or so I thought until recently.

By rule, the Belt and the Penny Society consisted entirely of seniors, and hazing season was precisely one week long. For the rest of their high school careers, most of the members and wannabe members marked time by avoiding school sanctioned athletics and clubs, earning D’s and F’s in citizenship—a C was a disgracefully high grade—and performing random acts of sliminess. For example, one day I inched closer to the front of the drinking fountain line when I realized that the person behind me was “George,” the meanest boy in the senior class. Tall and skinny, he owned the foulest mouth in the southern third of Indiana. I figured I’d better take one quick swallow and then hightail it out of there.

When I bent over to drink, George shoved me hard into the fountain, ramming the gum above my front teeth into the metal arch over the waterspout. The metal-on-gum collision instantaneously spewed blood into my mouth and forced involuntary tears to my eyes in much the same way biting your tongue does. George laughed. Ignoring the pain the best I could, I spat blood into the fountain and walked away, hoping he hadn’t seen the tears. Unfortunately, he had, and he told everyone I was a @%$*!!#% crybaby. In his mind, my pain was his gain. If I remember correctly, he was the 1957 hazing team captain, the Grand High Belter.

Hazing season was officially known as “freshman initiation week.” Team members may have looked like a disorganized detail of disagreeable and depraved delinquents completely lacking decorum for most of their high school careers, but for that one week their ability to follow unwritten hazing rules passed down by generations of hazers was awe-inspiring.

Every freshman had to push a penny with his or her nose one sidewalk block. Not a city block that consisted of many individual sidewalk blocks, but one little sidewalk block from crack to crack. That sounds easy enough, doesn’t it? Well, there was a little more to it. While the freshmen pushed that copper coin with their proboscises, they had to balance precariously on their knees with their hands behind their backs. Seniors, in a dazzling display of teamwork and grace, removed their belts and whacked the underclassmen’s posteriors. The velocity and frequency of the hits were directly proportionate to the degree hazers liked or disliked particular initiates.

Everyone knew the unwritten rules. Freshmen were initiated only once. A hazer always asked, “Have you been initiated?” If the answer was “no,” the freshmen took the classic initiation stance and braced for the belt-induced encouragement. If the answer was “yes,” the hazer asked, “Who initiated you?” He’d check with the person named, and if the freshman lied to avoid being initiated, he’d end up with a huge scab on his nose from thrusting it hard into the sidewalk every time a belt cracked his backside at lighting speed.

Everyone who had gone through the initiation in previous years told me to smile and get it over with because protesting would only make it worse. That’s what I did, and for the next five decades I found comfort in knowing that all my classmates had also experienced the belt and the penny.

When Ron, an old friend and classmate, visited Wisconsin Dells recently we met for breakfast, and I asked if he remembered who initiated him in the fall of 1957. That’s when he dropped a bombshell. He said he was heading back to school after lunch one day and saw others being initiated. When a hazer pointed at him, he turned and walked the other way. He was never initiated.

I was shocked. “I’m telling,” I said. He probably assumed I was kidding and that no sixty-five-year-old man could possibly be so petty and immature that he’d tattle on a friend over some high school event that happened—or in this case, didn’t happen—more than fifty years ago. Well, he assumed wrong. I can be exactly that petty and immature—even pettier and more immature if I put my mind to it.

So this is my tattle to the 1957 hazing team: Guys, you missed Ron during freshman initiation week. How could you have let that happen? I always thought you were outstanding hazers. Well, not any more. I’ve lost respect for the lot of you, but especially for you, George. You’re a disgrace to the belt and the penny.

A Boy Called Bird Legs

Mom never was much of an outdoors person, but during the late 1960s when she was in her fifties, she and Dad bought one of those huge, heavy canvas tents, stocked up on supplies, and took up camping. Indiana’s Turkey Run State Park north of Terre Haute and a little over a hundred miles from their Fort Branch home was one of their favorite destinations.

During one stay at Turkey Run, a troop of young Boy Scouts camping nearby took a liking to them and their longtime friends, Bud and Edna, who were camping with them. The boys hung out with them the entire weekend and even put on a skit Saturday evening and sat around their campfire for most of the night. Larry, a good-natured boy some of the others called “Bird Legs,” struck Mom as an especially nice boy. She often talked about the weekend the scout troop “adopted” them, and the boy she loved to tell about the most was Larry.

Fifteen years later, Bud and Edna stopped by my folk’s home for a visit. Bud pointed to a large picture in the sports section of the Evansville Courier on the coffee table that showed Larry Bird, then a famous Boston Celtic forward, taking a jump shot. “I’d say our little Larry Bird Legs has made it big.”

Mom glanced at the picture and nodded. “He certainly has.” She wasn’t a sports fan, but she knew who Larry Bird was, and she knew he was much more than just a basketball superstar. He was the man that good-natured boy called Bird Legs had become.

I was reminded of my parent’s encounter with young Larry when I read a Jeff Eisenberg article that told of Indiana State’s plans to erect a fifteen foot bronze statue of their most famous basketball player on the Terre Haute campus. Sculptor Bill Wolfe decided to make it taller than the twelve foot statue of longtime rival Magic Johnson that was erected at Michigan State.

Bud and Mom were right. That nice boy called Bird Legs has, indeed, made it big. A three-time NBA Most Valuable Player, he’s the only person in NBA history to be named Most Valuable Player, Coach of the Year, and Executive of the year. And he’ll always be exactly three feet taller than Magic Johnson.

Lessons Grandmother taught me

Bertha Nancy Brown, my maternal grandmother, lived from 1887 to 1969. I’ve graced the world with my presence since 1943. She taught me many lessons during the twenty-six years our lives overlapped. Today, I’d like to share five of them.

Lesson Number One: Home and school should always work together for the good of the child, or as Grandmother explained it to me, “If you’re spanked at school, you’ll be spanked again as soon as you get home.” Back in the forties and fifties, school spankings were common, and Grandmother wanted to make sure I understood that if I received one, it was my fault, not Bobby’s or Jane’s or the teacher’s. The purpose of the home spanking was to support the school’s efforts by reinforcing the point that I’m the only person in the entire world responsible for my actions. Views on corporal punishment have changed over the past sixty years, but Grandmother’s lesson is still valid. Simply change “spanked” to “disciplined.”

Lesson Number Two: There are clever ways to remember things. Spelling has never been one of my strong points. One evening, Grandmother noticed that the word “altogether” was one of many I had to write ten times because I’d misspelled it on a spelling test. “Mike,” she said, “I’m going to tell you a story that will make it impossible for you to misspell that word again.”

I was always happy to take a break from homework. I leaned back and listened to her story. “Billy, Ron, Al, and Suzie decided to set up a lemonade stand. Suzie said she’d run home and get some lemons. The boys waited and waited, but she never came back. Finally, Ron said to Billy, ‘We should send Al to get her.’” Grandmother wrote “Al to get her” on a piece of paper and underlined it . “So when you have to spell ‘altogether,’ just remember Al’s lemonade stand, and you’ll always spell it correctly.” I still misspell many words, but “altogether” isn’t one of them.

Lesson Number Three: Cure hiccups by taking exactly nine big swallows of water without breathing. Grandmother’s hiccup cure worked every time. I haven’t needed to use it for the last ten to fifteen years because the way I hiccup suddenly, mysteriously and permanently changed. I now hiccup only once, and that’s it. It’s amazing. I tell my wife that I “taught” myself how to hiccup only once, but the truth is it just happened, and I have no control over it. She hates my solitary hiccup because it sounds like a combination belch, gag, wheeze, and sonic boom.

Lesson Number Four: If you forget what you were going to say, go to the last place you remembered it, and you’ll remember it again. Like Grandmother’s hiccup cure, this works every time. Of course, I’m so forgetful, going to the last place I remembered something so I can remember it again has become my main source of exercise.

Lesson Number Five: There’s a portion of us that’s forever young. Grandmother put it this way: “There a young girl inside me.” I always felt sorry for that trapped girl and secretly hoped she’d escape, but now I know exactly what she meant. There’s a young boy inside me, too, and, when I let him, he still finds pleasure in simple things.

These five lessons Grandmother taught me won’t drastically change your life. But I’ll guarantee you one thing – you’ll never, ever misspell “altogether” again.

A long-overdue Thank You

I’d like to thank a man for something he did when we were first graders in 1949. He probably forgot about it a few days later, but I’ve never forgotten it.

Miss Walling had been teaching the value of nickels, dimes, quarters, and half dollars for days. Just before dismissing school one afternoon, she told us she would test our change-making knowledge the following morning. Only she didn’t use the word “test.”

“Tomorrow,” she said, “we will play store. I want each of you to bring a toy from home and write any price under a dollar that ends in a zero or a five on the tag I’ll give you. When I call your name, you will choose a toy and pay for it by selecting the correct amount of money from the bowl of coins on the table. Then, for the rest of the day, you can play with that toy during recess and free time.” She passed out the tags.

I ran home. “Mom!” I yelled just before the door slammed behind me, “I need a toy for store time tomorrow.”

“Store time?”

“Yeah. Everyone has to bring a toy. I don’t have anything to bring.”

“Sure you do,” she said. “You have all kinds of toys.”

“Not nice ones.”

Mom thought for a moment. “How about your dump truck?”

I ran to the backyard sandbox. I should have thought of the dump truck myself. I washed encrusted sand from my favorite toy and dried it with a rag. I wrote $.35 on the tag and tied it to the bumper.

The next morning, I placed my toy on the table in the front of the room. My heart sank. I had never realized how rusty and faded it was. It looked out of place next to the nice toys everyone else had brought. I walked quickly to my seat so no one would know it was mine.

When class started, Miss Walling drew a name, and a boy in the back of the room walked toward the table to select his toy. I slouched in my seat, prepared for a long, humiliating morning.

The boy paid for his toy from the money in the bowl, but instead of taking the direct route to his desk, he walked down my aisle. When he neared my desk, he held up a rusty truck for me to see and smiled. Somehow, he knew the toy was mine.

I don’t remember any of the other toys students brought that day. I don’t even remember the toy I picked or if I was smart enough to select the correct coins to pay for it. But I’ll always remember the boy’s thoughtfulness. He could have had any toy on the table, but he chose my old rusty truck over all the others.

I meant to thank him afterwards, but you know how it goes. Days turned into weeks that turned into months that turned into years that turned into decades. Now, I’m sitting at my computer typing the words “Thank You” that I should have said to him long ago, even though I know he’ll never see them.

I’m actually thanking him for two things. The first, of course, is for choosing the worst toy on the table that day. The second is for helping me understand that sometimes the seemingly insignificant things we do for others are remembered a lifetime.

Maybe You’re Left-Handed

My brother Don, older by nearly five years, is better than I am at almost everything. Of course, if you’d ask him if that were true, he’d modestly say it would be if the word “almost” were deleted. Over the years, he’s won about ninety-seven percent of our pool matches. I noticed something for the first time when we played pool during his recent visit. “Have you always shot pool left-handed?” I asked.

He pointed his cue stick toward a corner pocket and sank another shot. “Yep,” he said. “And there’s an interesting story behind it.”

I’d like to share with you the story he told me because it explains why a right-handed man shoots pool left-handed:

One day in March of 1951, thirteen-year-old junior high student Don McNair rode the fan bus to Princeton, Indiana, with a bunch of other students to root for the Fort Branch High School Twigs at the sectional. I’m not joking here, folks. We really were the Fort Branch Twigs. (For you slower thinkers, there’s a connection between “Branch” and “Twigs.”)

Mom naively assumed he’d spend the entire time in the Princeton gymnasium watching basketball games and singing “We’re cheering for you Fort Branch High – Rah! Rah!” with the rest of the fans, but you and I know that didn’t happen, don’t we? At some point, he and his buddies ended up at the Palace Pool Hall in beautiful downtown Princeton. Don had never been inside a pool hall before, and the thought that Mom might somehow find out gave him an uneasy feeling.

Most of the strangers that crowded the place were in their teens or twenties, but a few were older. Six or seven men in their forties, fifties, and sixties – probably pool experts – sat on high stools and watched the games, occasionally making comments. One, a stogie-smoking man with closely-cropped white hair and a missing front tooth, was the most vocal.

“Hey, kid,” he said, pointing his cigar at Don, “put your dime on the table and play the winner. Let’s see what you’ve got.”

Don placed a dime on the table. He’d never shot pool before, but how hard could it be? You hit the white ball with a stick, and it knocks a colored ball into whatever pocket you’re aiming for. They were playing Eight Ball. Even he knew the rules to that game.

“You’re next, kid.”

Don glanced at his opponent, a tall, skinny kid, perhaps sixteen years old, with a Chesterfield dangling from his mouth. He was about to play his first pool game ever, and against a big-city Princeton kid who knew how to smoke, no less. Don took careful aim and hit the white ball hard with the cue stick, but it didn’t knock the colored ball into the pocket he was aiming for. In fact, it didn’t hit the colored ball at all. It leaped right over it, bounced off the table, and rolled down the floor.

He heard the stogie smoker’s raspy voice over the laughter. “Hey, kid. Maybe you’re left-handed.”

Don figured the pool expert on the high stool knew what he was talking about, so he finished playing the first pool game of his life left-handed, as the man suggested, and has played left-handed ever since. He forgot about the pool guru’s comment until he was in his mid thirties. That’s when he finally realized that instead of giving him pool-playing advice, the stogie smoker was making him the butt of a joke.

“That’s funny,” I said when he finished his story. “I bet you never told Mom you played pool that day, did you?”

“Nope. Never did.”

I thought for a moment. “You know, I can understand your not telling Mom, but how come you never told me before now?”

“Because you were the world’s biggest tattletale. If I told you, not only would Mom know about it, the entire world would know.”

Don’s tattletale accusation hurt my feelings. What did he think I’d do – write a story about it that ended by emphasizing his inability to understand the difference between a snide comment and actual advice and post it somewhere where every man, woman, and child in the world could read it? Why, I’d never poke fun at Lefty.

Scouting, Fate, and the Presidency

The greatest single accomplishment a Boy Scout can achieve is becoming an Eagle Scout. To me the impressive part of becoming an Eagle Scout isn’t so much that final undertaking that results in reaching the top rung of the scouting ladder as it is all those other undertakings that lead up to that accomplishment. The totality of the undertakings teaches scouts to become leaders among boys and prepares them to become leaders among men. Did you know that several of our Presidents were Eagle Scouts?

I know how difficult many of the projects are because in the mid 1950s I was a Boy Scout in Fort Branch,

This is my Cub Scout pack back in the early ‘50s. I’m the second one from the left in the back row. I am protecting the identities of the other members because they may not want their children and grandchildren to know that they were members of this pack.

The details of my scouting failures are a little fuzzy fifty years after the fact. I do remember a bunch of us going for an overnight camping trip to New Lake, a little puddle of water five miles west of town. Several of us were to make Tenderfoot that night. To make it to that level, in addition to camping out all night, we had to make a campfire by ourselves using no more than two kitchen matches, and then cook our supper.

As a result of a heavy rain earlier that day, the ground and everything on it was wet. I gathered my firewood and after drying it the best I could by sliding it back and forth under my armpit, I carefully stacked each stick in ascending order according to size as I had been taught.

I struck my first match and held it to the kindling. The flame hissed and went out. I struck my second match and carefully inched the flame toward the kindling and held it there until it finally began to burn. However, after dancing tauntingly on the kindling for half a minute, the flame left and was immediately replaced by smoke. I vigorously fanned the kindling with my socks, but the flame never returned, and eventually the smoke that had taken its place laughed and went away as well.

I don’t know how many boys passed the Tenderfoot test that night, but I wasn’t one of them. While the others moved on to higher levels of scoutdom, I never retook that test. I never did reach that first rung of the Boy Scout ladder.

I think you should know that it was fate that kept me from lighting that campfire. Prior to becoming a Boy Scout, I was a Cub Scout. Although there were five Cub Scout packs in town at that time, fate placed me in the least macho of the packs. As you can tell from the picture, we had just finished a project making Easter bonnets. That’s right. While the other Cub Scouts were out fishing, telling ghost stories around the campfire, and snarfing down s’mores, we were making and wearing Easter bonnets. Do I look as if I’m being prepared to get that campfire started on the first or second try?

Just think about what could have been. Had it been my fate to be a member of a normal Cub Scout pack, I probably would have been prepared to start that campfire with the first match, which would have made me a Tenderfoot. Had I accomplished that, I probably would have achieved progressively more challenging scout goals until I made it all the way to Eagle Scout. We can only speculate where I would have gone from there. Probably like Gerald Ford and several others, I would have made it all the way from Eagle Scout to the Presidency of the United States. Today I could very well be sitting with my feet up in the Oval Office.

Makes you stop and think about the power of fate, doesn’t it? There were five Cub Scout packs in town when I was growing up, and I somehow ended up in the only one that could keep me from becoming the President of the United States.

Write your name on the old rusty spade

I’m telling you right up front that this article has an actual purpose. Lemonade is in danger of becoming extinct, and I need your help to prevent it from happening.

Chances are, you’ve never heard anyone say, “Write your name on the old rusty spade,” but just typing those words whisks me back to my childhood when days were perfect, anything was possible, and worries were light-years away.

The statement is from a children’s game called Lemonade, and I’m one of probably a handful of people who remembers it. In fact, I couldn’t find a single word about it on the Internet, and that’s a shame because it’s the perfect kids’ game. A combination of charades and tag, it involves teamwork, exercise, imagination, acting, sportsmanship, and friendship.

Rules are simple. Two teams, each with a home base safe-zone at opposite ends of the block, meet in the middle. The “it” team acts out a phrase its members make up, and the other team tries to guess it. When someone correctly guesses the phrase, the “it” team takes off running toward their home base. Members of the other team chase them, and every child they tag becomes a part of their team. The game continues, with teams taking turns being “it,” until everyone ends up on the same team.

On a beautiful June afternoon in 1951, my team came up with the perfect “Five-W” phrase, and I invite you to relive that moment with me.

We always played Lemonade on the Foster Street sidewalk. Foster is only one block long, but when I was eight, it was the center of the universe. My team’s home base is way down at the east end of the block by Larry’s house. The other team’s home base is on the west end by Billy Earl’s house. The game starts in the block’s exact middle.

That’s me, the dopey-looking kid with the giggles. I’m having a hard time concealing the fact we just made up the perfect phrase. The other team waits at the starting point. We march to them and stop. They recite the required chant in unison. “Lemonade, lemonade. Write your name on the old rusty spade.”

Millard digs a piece of chalk from his pocket and prints the first letter of each word in our perfect phrase on the sidewalk – WWWWW – and we act out the words. We pretend to dip a cloth into a water bucket and wash a window, which we draw in the air with our fingers by making a square with a cross in the middle. We hold up our one finger and act presidential. We pretend we’re getting wet from rain by wiggling our fingers and moving our hands toward us. We make-believe we’re a couple getting married and point toward the imaginary bride next to the presidential-acting boy who’s holding up one finger to signify “first.”

Finally, someone shouts the correct answer, “Washing Washington’s Wife’s Wet Window’s,” and we take off running as fast as we can. The other team chases us, but we all make it back to home base by Larry’s house without being tagged. The game continues.

Here’s how you can help keep Lemonade from becoming extinct. The next time you make a list of games for kids to play at a birthday party or family reunion, put Lemonade at the top. It’s unlikely they’ll come up with the perfect “Five-W” phrase like my friends and I did, but I guarantee if they like the drink, they’ll love the game.